Can you resell software licenses? The latest legal position in 2016

This is a guest post from Robin Fry of Cerno.

The European Court has restated the legality of the resale of software in Europe in its latest judgment but confirmed that the principle does not extend to software transferred on back-up discs.

The October 2016 ruling is the first by Europe’s highest court since its seminal 2012 decision concerning Oracle programs which effectively equated software downloaded from the internet with physical products. This brought in, for the first time, the legal possibility of the resale of business software – even where the license agreements signed up to by the licensee declared that the software was non-assignable and only for that particular licensee’s internal business purposes.

Robin Fry, Cerno PS – “Furthermore support costs on software (20-22% per annum of purchase price) generally exceed, over time, the initial license fees paid. This means that, if there were a new user of redundant software, then there is the possibility of extending the vendor’s customer base and increasing, rather than damaging, its income.”

Since 2012, a number of brokers have been formed but the silence around this issue has done little to reassure owners of surplus software licenses and shelfware that, yes, indeed, licenses can be marketed and sold on.

The July 2012 judgment in the ‘UsedSoft’ case stated, in summary, that the distribution right held by the software vendor was ‘exhausted’ within the EU provided certain conditions were met: that the software license was perpetual, that it had originally been sold at an economic price, and the seller’s copy was made unusable at the time of transfer.

The latest case followed 12 years of investigation by Microsoft with criminal proceedings being brought against a Latvian reseller, ‘Soft Home’ in respect of Microsoft Windows and Office software sold on eBay. Fake Certificates of Authenticity and labelling had been created with the software being supplied on duplicate discs copied over from original OEM discs supplied with PCs or back-up discs obtained without transfer of the related hardware.

The two directors of Soft Home, Aleksandrs Ranks and Jurijis Vasiļevičs, had marketed and sold pirated copies of Windows 95, Windows 98, Windows 200 Professional, Windows Millennium, Windows XP, Office 200 Professional and Office 2003 Small Business netting US$300,000.

The individuals were finally found guilty by the Latvian criminal courts in January 2012 but, following multiple appeals, there was a referral to the European Court in April 2015 requesting clarification of the 2012 ‘UsedSoft’ case: just possibly this might give a way out for the two defendants.

In fact, the referral to the court failed to assist these two and it firmly stated that legal resale could not be effective by the use of back-up discs E.g. those delivered with OEM installed software without Microsoft’s consent.

The court ruled that:

‘although the initial acquirer of a copy of a computer program accompanied by an unlimited user licence is entitled to resell that copy and his licence to a new acquirer, he may not, however, in the case where the original material medium of the copy that was initially delivered to him has been damaged, destroyed or lost, provide his back-up copy of that program to that new acquirer without the authorisation of the rightholder.’

That ruling has put a stop to a grey market in OEM discs separated from the downloaded software; it could never have been a part of the new legal market. What however is the current position?

To date – and predictably – the software vendors (and indeed authorised resellers) have not been interested in mentioning the possibility of resales to their customers. If asked, they prefer to intimate uncertainty as to the legal position and doubts as to support. But with a combination of legal, technical and commercial advice, buyers and sellers can successfully navigate this area and obtain high cost savings.

The software vendors cannot be too dismissive: they are constrained by competition (anti-trust) laws in seeking to inhibit the market in indirect ways. This can include discriminating against their customers, refusing support or seeking higher prices from those using pre-owned software. The jeopardy for them is a finding of abuse, damages and fines of up to 10% of their group’s global turnover.

Over the last four years, there has been some low-level litigation in the German and Dutch provincial courts but there have not been found any flaws in the UsedSoft case. Paradoxically, it was the company UsedSoft itself that could not comply with the core requirements for valid transfer when the case reverted back to the German court after the European Court’s statement of the new law.

All the major software vendors are focussed very strongly now on moving their customers to cloud services. Logically, one might argue that the cost to switch from installed systems using perpetual licenses to cloud services (no such licenses needed) would be far less if the customer were told that value in its redundant licenses could be obtained by reselling.

Furthermore support costs on software (20-22% per annum of purchase price) generally exceed, over time, the initial license fees paid. This means that, if there were a new user of redundant software, then there is the possibility of extending the vendor’s customer base and increasing, rather than damaging, its income.

The determined focus on cloud services may, in part, explain why the vendors have not altered their software licenses by changing perpetual terms to shorter E.g. 10-year licenses which would then arguably have taken these licenses outside the scope of the UsedSoft regime. But the vendors will also have looked at their revenue recognition policies and seen that any switch to restricted-period licenses would severely affect the value of declared new license revenue.

There has been negligible visibility as to the options for used software. However, with the latest ruling by the European Court, and the few pieces of litigation against brokers ended, the position is far more certain and the public market may begin to develop more prominently.

This is a guest post from Robin Fry of Cerno.

Further reading:

Original EU Court of Justice ruling, July 2012.

Can’t find what you’re looking for?

More from ITAM News & Analysis

-

Stop Shadow IT Before It Hurts Your Business

Shadow IT often spreads quietly and quickly becomes a serious risk. Just look at the UK-based supermarket chain Co-op. A little-known remote maintenance tool used by an external IT provider was compromised. The result? Nearly 800 ... -

Why ITAM Forum Should Join the Linux Foundation: My Rationale and Your Questions Answered

TLDR. ITAM Forum has the opportunity to join the Linux Foundation as a stand-alone, self-funded project. This article covers a) What’s happening b) Why I think it’s a great move for the ITAM Forum and c) ... -

Microsoft Pricing Changes: EA Customers Face Price Increases

From 1st November 2025, Microsoft will remove all tiered pricing for Online Services under the Enterprise Agreement. This means all customers renewing or purchasing new Online Services after this date, will receive standard level A pricing ...

Software Licensing Training

Similar Posts

-

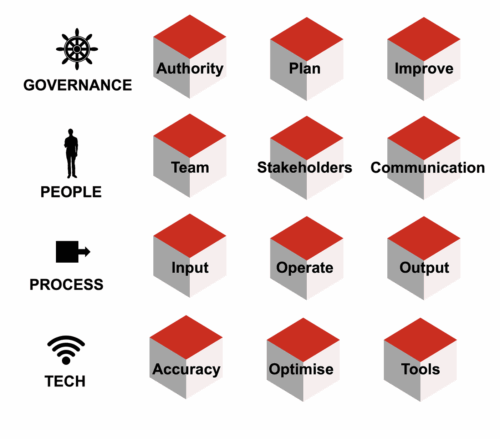

Eight steps towards AI governance

I delivered our “Managing AI as an Asset” training course the day before the Wisdom conference last week. Thank you to those who attended and provided feedback. It will be available on the LISA platform before ... -

Crawl, Walk, Run applied to ITAM Best Practice (Practical ITAM)

Since the ITAM Forum has been working in strategic partnership with the FinOps Foundation, I’ve come to admire the Crawl, Walk, Run approach to best practices, as it allows improvements and recommendations to meet the organisation ... -

Stop Shadow IT Before It Hurts Your Business

Shadow IT often spreads quietly and quickly becomes a serious risk. Just look at the UK-based supermarket chain Co-op. A little-known remote maintenance tool used by an external IT provider was compromised. The result? Nearly 800 ... -

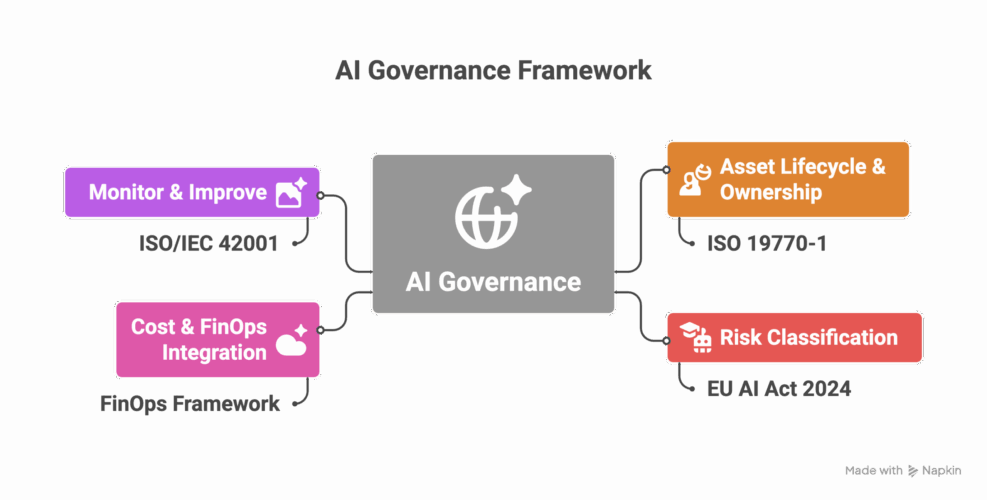

AI Governance Through an ITAM Lens: Treat AI as a Status Change, Not a New Asset

Managing AI in the enterprise is a team sport. In this article, I want to explore specifically what ITAM brings to the table as we enter the AI era. As I’ve mentioned in previous articles on ...