Managing Office 365: ITAM meets Identity Management

Daniel Power, Onelogin

This article has been contributed by Daniel Power at OneLogin

The official end-of-life for Microsoft Windows Server 2003 is fast approaching, and with 11 million estimated to still be in use, there is an increased focus on the future infrastructure of corporate email systems. Alongside this, Exchange Server 2003 is probably the most widely installed platform supporting internal email systems; according to the Radicati Group, 85 percent of all corporate email boxes are delivered via on-premise systems, and Microsoft is clearly the major player in that market. So the demise of Server 2003 has much potential to complicate the lives of IT asset managers and for many organisations, it will be the straw that breaks the on-premise camel’s back, pushing core infrastructure software to the cloud.

While Microsoft enterprise customers have the option to stay on-premise by upgrading to Exchange Server 2007 or 2010, many will choose to move some or all of their Microsoft productivity applications to the cloud with Office 365, which includes both managed and self-support email options. Microsoft is encouraging business customers to move to the cloud and pushing its own business model from traditional licensing to subscription-based revenue streams. For many organisations Microsoft licensing fees are their largest IT software expenditure, so fundamental changes to Microsoft licensing arrangements must be carefully planned long before making acquisition and transition decisions.

Office 365 licenses – navigating the complexities

Moving to the cloud will change the way you think about software licensing, because the majority of licenses are linked to users rather than devices. Office 365 checks from the cloud that each user has not breached the per-user limit by installing device-resident versions of the Office suite on more than five devices. Secondly, because you have easy access to usage data in the cloud, you can more easily identify unused subscriptions within the licenses you’ve purchased.

A core factor, which will drive Office 365 licensing plans, is the lack of parity between the on-premise and cloud-based options. Office 365 licensing options and capabilities differ across the different flavours of implementation: on-premises Office 2013, SharePoint, Lync, and Microsoft Exchange are all affected. SharePoint is a particular case in point here, as many organisations have invested heavily in custom development and third-party integrations around the collaboration platform which will all need to be rewritten, and associated licences renegotiated, to move to SharePoint online as part of Office 365.

Take particular care with SharePoint migration

SharePoint Online is also looking less useful as a portal platform than its on-premise cousin, as Microsoft is discouraging customisation during the transition in favour of a standardised experience. While this approach may work just fine for small businesses, it is likely to prove a major handicap for enterprise IT departments that have built custom integrated environments around SharePoint. There’s also a push towards greater use of enterprise social network platform Yammer in SharePoint and Office 365, but Yammer is cloud-only and very much an internal-facing tool, without the customer-facing web capabilities and integration with CRM, e-commerce, customer support, and marketing automation systems most enterprises expect.

Complex licensing carries significant financial implications

SharePoint is also widely used in conjunction with Microsoft Project, but this is where we start to see the licensing complications of moving to Office 365. While each Office 365 licensing plan includes Exchange Online and SharePoint Online as core individual services, Project Online is a separate add-on service, and Yammer Enterprise is missing from a number of licence configurations offered, particularly in the areas of government and education. Azure RMS is not included, but can be purchased as an add-on service. While individual licensing plans can be mixed and matched within a service family – for example, you can move from Office 365 Small Business to Office 365 Enterprise E3 – you cannot move from the Enterprise service family to either the Midsize or Small Business service family.

There can also be significant financial implications to your choice of migration route. While Office 365 Add-ons are a simpler way to contract for Office 365 than Transitions, they can be almost 24 percent more expensive than Transitions. So if you’re converting from on-premise, user-based licences to cloud licences, the Transitions route can deliver big savings.

License management and tracking challenges

While you can keep changing the plan to meet changing needs of the organisation, you still need an effective way to keep track of all those licences/user rights, both in the cloud and on-premise. The time to build that tracking system is before you even start the migration.

In preparation for the process, you’ll need to:

- Segregate your users to figure out the licence types you’re going to need

- Model the role-based access needed for all applications. This includes not just cloud-based apps, but on-premise apps as well

- Create a process for provisioning and deprovisioning users and licenses

- Automate as much as possible, including regular reports to ensure you’re not paying for more subscriptions than you’re using

Work with your IT teams to map your options and strengthen your asset management processes to ensure you have the flexibility to track and manage a hybrid licensing system as you begin the process of transitioning core application software to the cloud. Microsoft’s huge range of options and choices does not make the process easy!

Consider centralised identity and access management

As cloud application licensing is based on the user, not their machines, it’s important to know when and how users are engaging with each application. Centralising the application access and user management process as part of the transition to Office 365 can assist with:

- Managing onboarding and offboarding access in a timely and secure manner

- Providing a centralised location to track SaaS portfolio use across the business to optimise SaaS seat utilisation

- Pairing users with appropriate licences within multi-module applications like Office 365. For example, business development staff would automatically get specific licence types within Office 365 such as Yammer, SharePoint Online and Microsoft Communications. The product development team would also get Microsoft Project Online.

Additionally, centralised licence management helps with licence renewal negotiations, since you have access to real usage numbers, as well as compliance auditing and reports. Single-user multi-device access means that counting installations does not prove license compliance and the onus is on you, the customer, to prove you’re entitled to use all the licences you’re consuming. So those records need to be managed and maintained as close to real-time as possible.

Choosing the right identity management model for Office 365

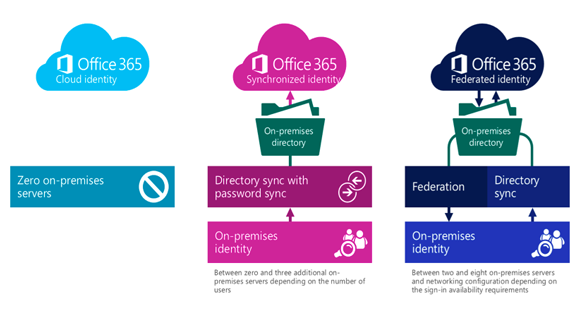

Centralising identity and access management can take several forms, and Microsoft has defined three general models:

- Cloud Identity: Under this model, businesses have a siloed set of identities inside an Azure Active Directory (AD) tenant that comes with Office 365. In other words, there’s yet another set of usernames and passwords to manage.

- Synchronised Identity: This model is a one-way sync between your on-premises Active Directory and Office 365. It’s an improvement over Cloud Identity as users are using the same username and password, but they do have to re-enter them.

- Federated Identity: In this model, Active Directory stores and controls security policy. When users are authenticating, there’s a real-time check against AD. In other words, users don’t have to re-authenticate if they are on the corporate network.

If you want real-time authentication based on AD, are looking for desktop single sign-on (Integrated Windows Authentication), have a complex directory infrastructure, or require more advanced compliance reporting capabilities, then federation is probably where you’re going to end up.

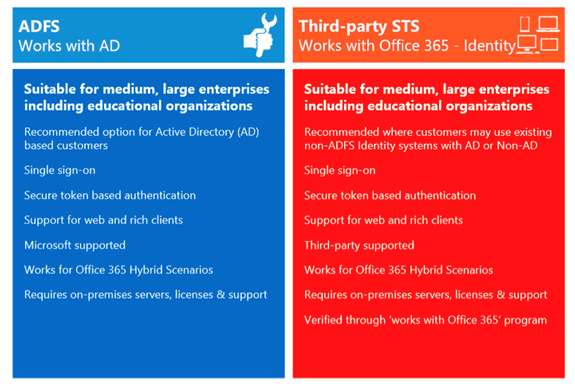

Assuming you’ve made the choice to go the federated route, then there are two main “Microsoft sanctioned” options – Active Directory Federation Services and Third-party Security Token Service – as shown in the graphic below from Microsoft:

Microsoft’s native solution based on integrating ADFS and Azure AD

Depending on your specific needs, there can be a lot of pieces to the Microsoft puzzle that complicate federation. In order to federate Active Directory to Azure AD and Office 365, you’re still going to need ADFS, and other Microsoft components such as DirSync, Forefront Identity Manager (to handle mixed directory types), and Multi-Factor Authentication Server.

Keep in mind that the 99.9+ percent uptime guarantees with your SaaS vendors are meaningless unless you’re able to achieve the same uptime with your ADFS infrastructure. A highly available ADFS deployment is predicated on load balancing multiple sets of servers, and may even require deploying SQL Server (or a SQL Server Cluster), a storage solution, and a global traffic management solution.

Microsoft’s Works with Office 365 Programme

Microsoft also supports integration with third parties through a programme called Works with Office 365. Identity providers that have been accepted into this programme have passed a series of federated identity and single sign-on interoperability tests across different Office 365 clients.

Your apps are moving to the cloud so why not identity management?

In moving a major application platform to the cloud, it makes sense to consider investing in cloud-based IAM at the same time. Additionally, third-party solutions, such as OneLogin, can offer advantages over the all-Microsoft approach by simplifying the integration of new apps and supporting directory structures beyond AD.

The start of something big

Migrating core productivity software like Office to the cloud is attractive because of its lower costs, ease of deployment, instant software updates, and license management. That said, centralised identity and asset management will be essential to the sanity of all concerned as the mass migration of enterprise infrastructure to the cloud picks up speed – and you will not be able to do this with traditional software asset management inventory agents. Once you know who’s using what software and can track how that usage changes over time, you’re also in a far better position to plan for future cloud versus on-premise decisions.

This article has been contributed by Daniel Power at OneLogin

Can’t find what you’re looking for?

More from ITAM News & Analysis

-

Broadcom vs Siemens AG - A Brewing Storm

The ongoing legal battle between VMware (under Broadcom ownership) and Siemens is yet another example of why ITAM goes far beyond license compliance and SAM. What might, at first glance, appear to be a licensing dispute, ... -

Shifting Left Together: Embedding ITAM into FinOps Culture

During one of the keynotes at the FinOps X conference in San Diego, JR Storment, Executive Director of the FinOps Foundation, interviewed a senior executive from Salesforce. They discussed the idea of combining the roles of ... -

Addressing the SaaS Data Gap in FinOps FOCUS 2.1

I recently reported on the FinOps Foundation’s inclusion of SaaS and Datacenter in its expanded Cloud+ scope. At that time, I highlighted concerns about getting the myriad SaaS companies to supply FOCUS-compliant billing data. A couple ...

Podcast

ITAM training

Similar Posts

-

The M&S Cyberattack: How IT Asset Management Can Make or Break Your Recovery

Marks & Spencer (M&S), the iconic UK retailer, recently became the latest high-profile victim of a devastating cyberattack. Fellow retailers The Co-Op and Harrods were also attacked. Recent reports suggest the rapid action at the Co-Op ... -

AI in ITAM: Insightful Signals from the Front Line

During our Wisdom Unplugged USA event in New York in March 2025, we engaged ITAM professionals with three targeted polling questions to uncover their current thinking on Artificial Intelligence—what concerns them, where they see opportunity, and ... -

How ISO/IEC 19770-1 Can Help Meet FFIEC Requirements

In the world of ITAM, the regulatory spotlight continues to intensify, especially for financial institutions facing increasing scrutiny from regulatory bodies due to the growing importance of IT in operational resilience, service delivery, and risk management. ... -

An Introduction to Scope 4 Emissions

Executive Summary For ITAM teams, sustainability is a core responsibility and opportunity. Managing hardware, software, and cloud resources now comes with the ability to track, reduce, and report carbon emissions. Understanding emission scopes—from direct operational emissions ...