A Twitter thread by a Netflix engineer gives a great insight into some of the intricacies of cloud – in this case Amazon AWS – and how even those who know what they’re doing don’t always get it right!

Background

The engineer tells us that most deployments at Netflix use the red/black strategy within Spinnaker. Before we go any further, let’s cover the 2 obvious questions:

What is Spinnaker?

Spinnaker (not to be confused with Spinnaker Support) is an open source product that helps organisations quickly release software changes in a multi-cloud environment. It was created at Netflix and is now used by a host of companies including Microsoft, Google, Target, and more – perhaps your organisation uses it?

What is the red/black strategy?

This is a method of deploying new versions of your service alongside the current live version – giving a simple rollback procedure, making it easy to return to a “last known good version”. You essentially run two production environments, a live and a test version, that are kept separated.

Back to Netflix

One potential problem of this method is automated scale down. If the 2 environments are live for a long period of time, as neither is receiving the full amount of traffic for which it is designed, they will start to shrink to fit themselves to their actual usage. However, that means when the switchover is finally made – and all old system is turned off, the new environment will find itself under-provisioned to cope with the entire traffic load.

Pinning

To combat this, Netflix “pin” the server groups – that is, set a minimum size for the system. However, the Netflix engineer noted they only pin the new group – leaving the old group free to scale down, which could cause issues in the event of a rollback. He decided that pinning both groups would be a good idea and, after a period of testing, turned the change live.

What happened?

Due to “an ordering of operations issue”, the change caused every new server group to stay pinned. That perhaps doesn’t seem like too much of an issue, after all – how often can new server groups be deployed? Well, according to the Spinnaker site, Netflix makes over 4,000 deployments a day!

The changes made in this situation didn’t throw up any errors but did cause Netflix to have “about 600 server groups” deployed that had “about 10,000” extra instances in Amazon AWS that couldn’t scale down properly. The situation existed for around 24 hours before being rectified.

Costs

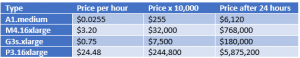

I don’t know how much each instance cost Netflix but a few possible examples of Linux virtual machines using on-demand pricing look like this:

Whichever type of instance was involved, I’m sure Netflix use Reserved Instances to keep their costs down, but this situation shows the how a simple change can quickly result in increased spend.

What does this mean for ITAM?

Whatever the final cost for Netflix, this is a great example of how the best laid plans can go awry. The nature of the cloud means that additional money is spent immediately. It’s not like on-premises where an accidental over-deployment of SQL Server or Oracle DB2 could be identified and uninstalled without incurring costs…the additional spending is happening in real time.

I’m in no way advocating that ITAM become deeply involved in software deployment strategies, but I do think – as cloud becomes an ever-bigger part of our world – that it pays to be aware of these potential hazards. When you’re working with stakeholders around the business to decide on cloud budgets and attempting to predict cloud spend over the next 1/3/5 years – knowing to ask about these types of things could help put you in a strong position internally, and to mitigate potential overspend before it occurs.

Further Reading

Engineer’s original story – https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1106714429247221761.html

Spinnaker – https://www.spinnaker.io/

Netflix deployment count – https://www.spinnaker.io/workshops/

AWS EC2 pricing – https://aws.amazon.com/ec2/pricing/on-demand/

Thanks for sharing this article as its a great example of how easy it is to suddenly find yourself in trouble in these environments.

Rich, this is an insightful story. Thanks for simplifying and breaking down the problem.