Don’t let cloud adoption fool you – VMware are still relevant

It’s easy to think, in these days of ever greater cloud infrastructure adoption, that VMware doesn’t have the clout they once did in the IT world. In fact, I recently had a client demote the vendor from their top 20 list, where they’d sat for many a year. More businesses are moving to Azure and AWS than ever before, IaaS usage is growing at an exponential rate, and cloud is, as we all know, very much the buzz word of the decade. And it will be for some time to come. But don’t write off the world’s largest provider of ‘traditional’ (some might say legacy) on-premise datacentre virtualisation just yet.

In the money

A cursory look at their financial results for 2018-19 shows annual revenues of nearly $9 billion, a 14% increase on 2017-18 and, by the way, a record for VMware. Q4 (November – January) accounted for nearly a 3rd of that with $2.6 bn, an increase of 16% on the same quarter the previous fiscal year. License revenue was responsible for just under half of Q4’s revenue but, again, there was a significant increase, year on year, of 21%. The fact that the licensing was only half the quarter’s revenue tells you everything you need to know about where VMware is making a lot of its money – support, professional services and, increasingly – wait for it – cloud subscriptions.

VMware in other people’s clouds

You probably already know that VMware have tied up deals with Amazon AWS and Microsoft Azure, alongside all of their other VMware Cloud Foundation providers; and it was recently announced that Google are joining that particular cloud party too. So, what’s the point of these partnerships? Two words – hybrid cloud. Hybrid cloud is a term used to describe a technology platform comprised of 1 or more cloud services (IaaS usually) and on-premises datacentres. In the context of VMware, it very much involves the data centre. To be clear, though, these partnerships do not follow the usual rules of public cloud services.

How it works

When you are buying an IaaS service on Azure, AWS, or Google Cloud, you are normally subscribing to the use of one or more VMs on their shared server platform in one of their global datacentres. With the VMware hybrid scenario, however, the “public” cloud element is actually hosted on dedicated servers. The beauty of this approach to technology hosting is that you can effectively run your own VMs, which may have been deployed on-premise in your own vSphere-based datacentre, natively on the cloud providers’ platforms. You can, therefore, use the this approach to protect your investment in on-premise VMware licensing, by continuing to use your licensed products in your datacentre, whilst taking advantage of the benefits of public cloud offerings – application scalability, offsite DR scenarios and rapid scalability when required for spikes in demand.

Licensing & Pricing

As far as paying for it goes, you would still need to licence the on-premise part of the solution with VMware through the usual channels – whether that be an ELA, EPP or other licensing program. The cloud side of the platform is paid for, unsurprisingly, via subscription. Though instead of subscribing to VMs, as may be the usual case if your organisation already has a cloud presence, you subscribe to the number of physical host server CPUs your technology is consuming. Another benefit to note, is the licensing angle. Because the Azure, AWS or Google cloud servers involved in this unified technology platform would NOT be shared servers, the Bring Your Own Licence policies offered by many software vendors are obviated. That said, Microsoft have recently extended the need to have SA to dedicated cloud platforms, as well as shared, so you would still need to watch out.

Further Info

Barry delivers a comprehensive VMware licensing training course as part of our LISA training platform. You can check it out with a free trial here https://lisa.training/free-trial/

Can’t find what you’re looking for?

More from ITAM News & Analysis

-

Stop Shadow IT Before It Hurts Your Business

Shadow IT often spreads quietly and quickly becomes a serious risk. Just look at the UK-based supermarket chain Co-op. A little-known remote maintenance tool used by an external IT provider was compromised. The result? Nearly 800 ... -

Why ITAM Forum Should Join the Linux Foundation: My Rationale and Your Questions Answered

TLDR. ITAM Forum has the opportunity to join the Linux Foundation as a stand-alone, self-funded project. This article covers a) What’s happening b) Why I think it’s a great move for the ITAM Forum and c) ... -

Microsoft Pricing Changes: EA Customers Face Price Increases

From 1st November 2025, Microsoft will remove all tiered pricing for Online Services under the Enterprise Agreement. This means all customers renewing or purchasing new Online Services after this date, will receive standard level A pricing ...

Software Licensing Training

Similar Posts

-

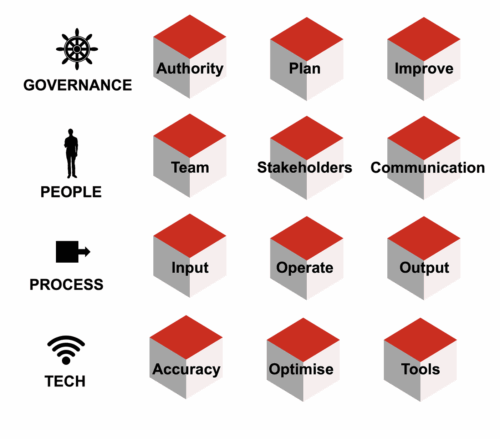

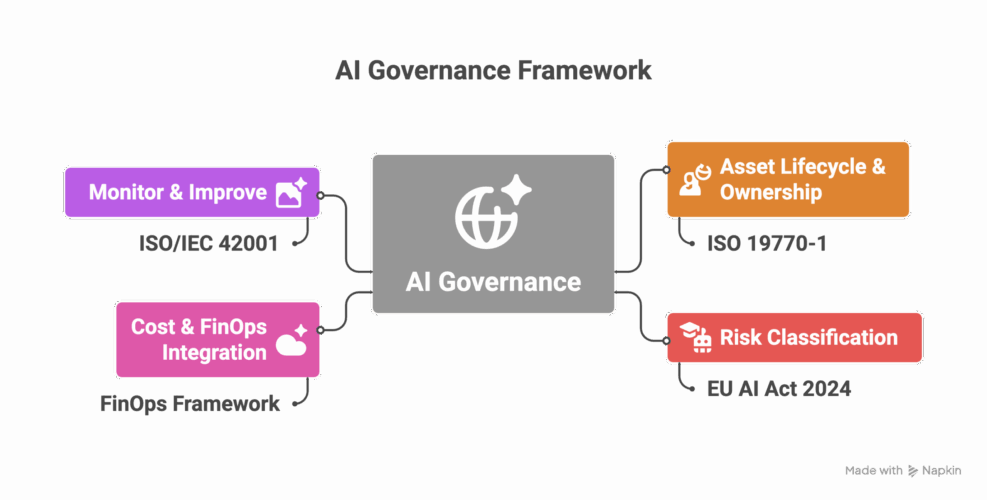

Eight steps towards AI governance

I delivered our “Managing AI as an Asset” training course the day before the Wisdom conference last week. Thank you to those who attended and provided feedback. It will be available on the LISA platform before ... -

Crawl, Walk, Run applied to ITAM Best Practice (Practical ITAM)

Since the ITAM Forum has been working in strategic partnership with the FinOps Foundation, I’ve come to admire the Crawl, Walk, Run approach to best practices, as it allows improvements and recommendations to meet the organisation ... -

Stop Shadow IT Before It Hurts Your Business

Shadow IT often spreads quietly and quickly becomes a serious risk. Just look at the UK-based supermarket chain Co-op. A little-known remote maintenance tool used by an external IT provider was compromised. The result? Nearly 800 ... -

AI Governance Through an ITAM Lens: Treat AI as a Status Change, Not a New Asset

Managing AI in the enterprise is a team sport. In this article, I want to explore specifically what ITAM brings to the table as we enter the AI era. As I’ve mentioned in previous articles on ...